This month, I signed a pledge to donate at least 10% of my lifetime income to effective charities. And this week, I decided to donate 19% of my annual income, with more than 80% to a charity working in Nigeria to complete a water and sanitation project. The project was being funded by USAID, but that funding was suddenly canceled by the Trump administration without notice.

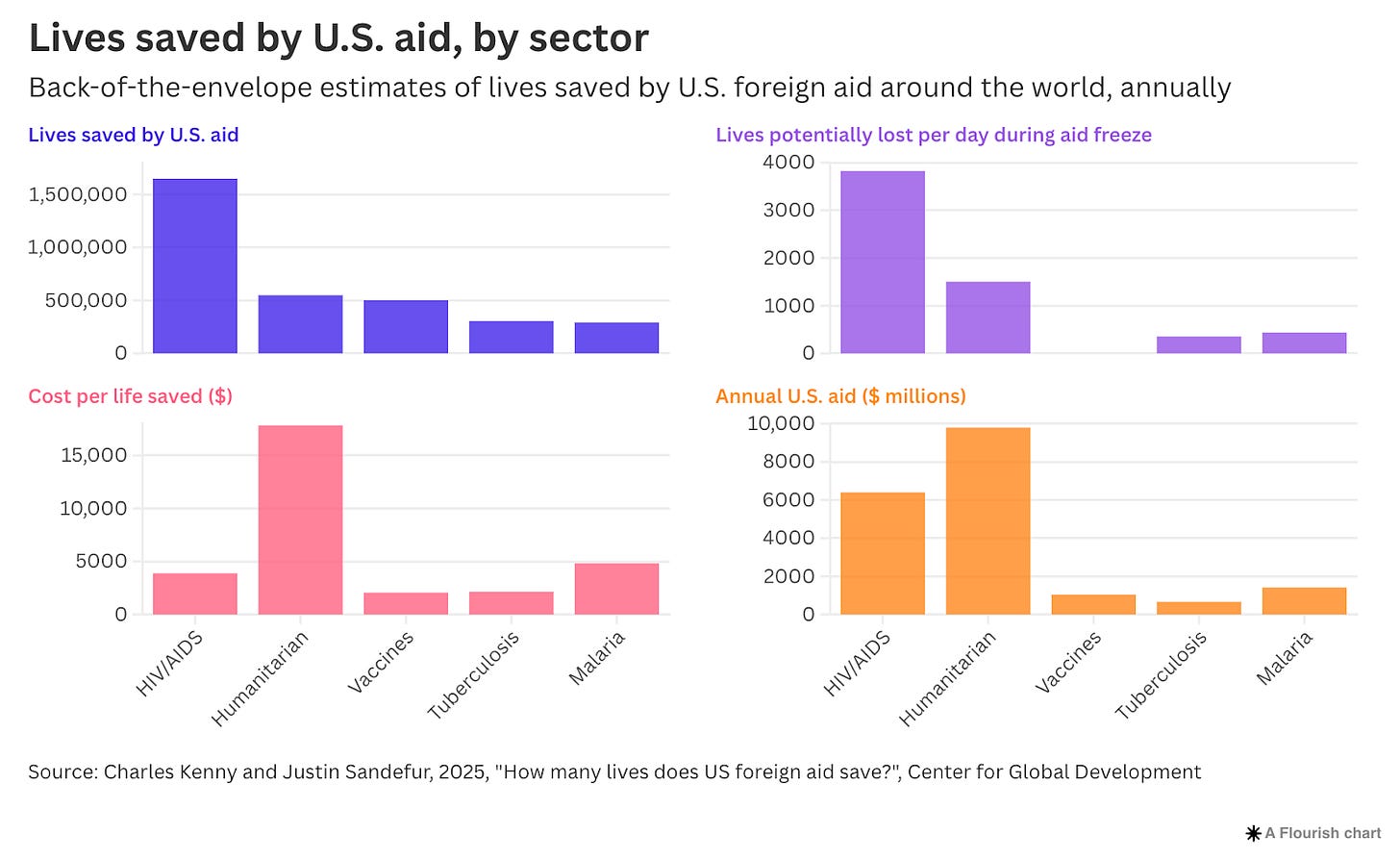

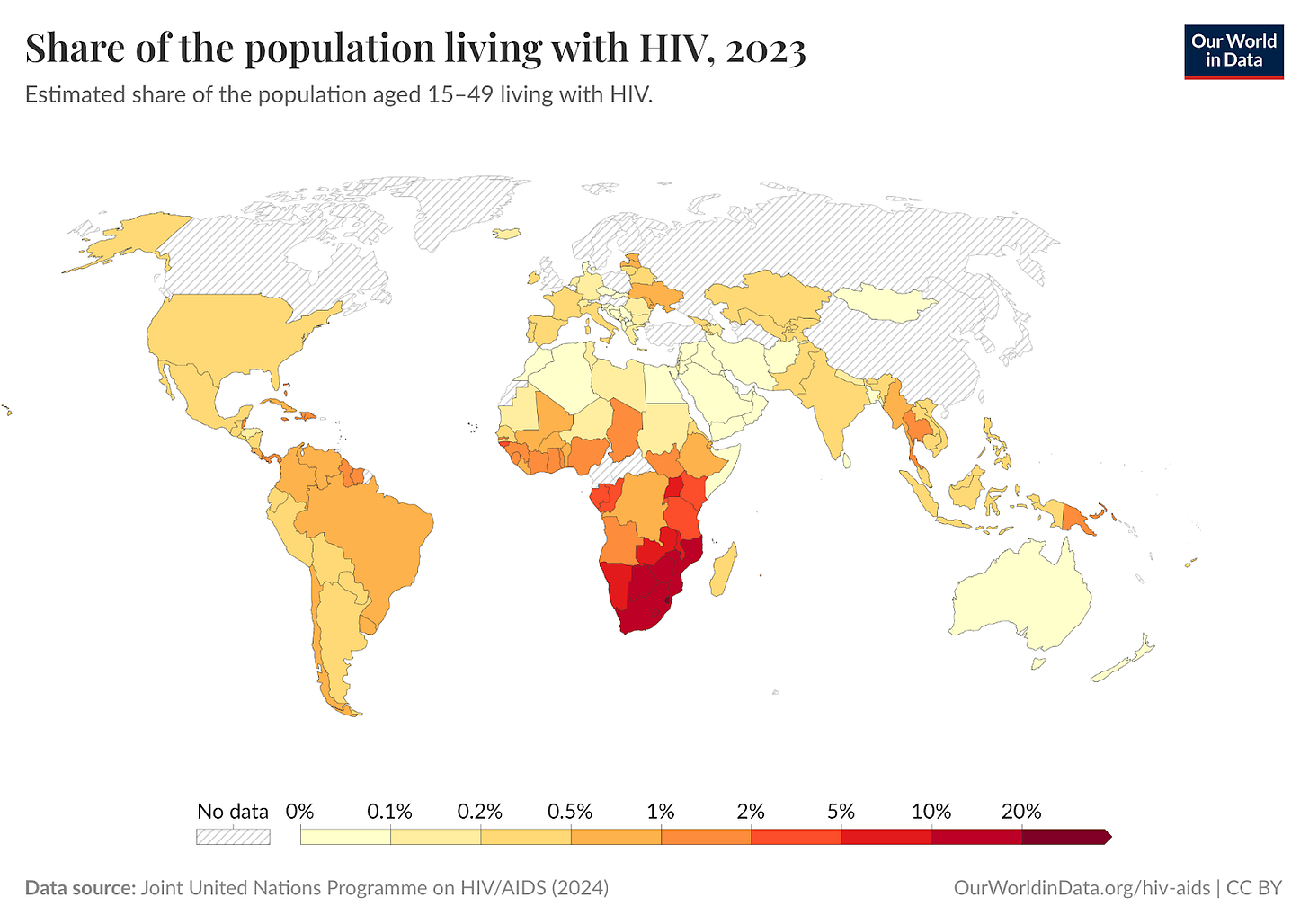

In recent months, US foreign aid programs have been slashed. It’s hard to wrap your head around the scale of these programs. The largest, PEPFAR, has provided HIV treatment and prevention to 20 million people annually – mostly in Africa, but also in other countries around the world – and is estimated to have saved around 25 million people since it began. It was launched by the Bush administration in 2003. Another one is PMI, also launched by Bush, which provides antimalarial bed nets and treatment to tens of millions of people each year, and is estimated to have saved more than 10 million lives since it began.

Many people don’t know how important global health programs have been to people around the world despite costing only a tiny fraction of our incomes in richer countries.

Even aside from HIV/AIDS and malaria, we’ve almost wiped out polio worldwide thanks to global vaccination campaigns. Deaths from tetanus have fallen more than seven-fold in three decades. Millions of children have been effectively treated for trachoma, a painful bacterial infection that can cause blindness. But many people haven’t heard of these achievements. Maybe that’s why it can all seem distant and abstract, not real and urgent.

The disruptions started at the end of January when the US froze all foreign aid programs to conduct a “three-month review.” But since then, many programs tackling HIV, malaria, and other global health efforts have been permanently canceled. The US also withdrew all their funding for Gavi, which provides vaccines against polio, measles, diphtheria, cervical cancer, and many other diseases, for millions of children in poorer countries.

Given the scale of these programs, the impact of the disruption was immense. With PEPFAR serving tens of millions per year, hundreds of thousands were losing access to HIV treatment per day.

What does that actually mean? In many cases, clinics had lifesaving antiviral treatment on their shelves, but were asked to shut down. USAID staff were laid off, programs were no longer being paid, and procurement of more supplies had stopped as well. Suddenly, hundreds of thousands of people – every single day – were finding out they could no longer get their next round of HIV treatment.

In Africa, over 60% of people living with HIV/AIDS are women. Around a million are pregnant. But today’s antivirals are so effective that if taken during pregnancy, the risk of passing HIV to the infant is minimal. Without these drugs, around a quarter of babies born to HIV-positive mothers would also contract the virus – and half of them would die before the age of two.

The freeze meant over a thousand more newborns were contracting HIV every day, because their mothers had lost access to treatment: without warning, through no fault of their own, and often, with no alternatives.

The economists Charles Kenny and Justin Sandefur estimated that around 6,000 people would die per day from a complete US aid freeze, which was the case during the “90-day pause”. They estimate that around 3.3 million would die if it continued for a year. I find it hard to understand how this could happen at such a scale. It’s terrifying to try to imagine.

Around a third of the local organizations running PEPFAR had completely shut down during the freeze because they were unable to secure replacement funds and staff. Less than 10% restarted providing treatment weeks later.

Then, all of a sudden on March 10th, the Trump administration announced the review was completed, in 35 business days. They “made a final decision with respect to each award, on an individualized basis,” to terminate 8,644 State and USAID awards. As the economist Charles Kenny put it, “That’s about one award every minute and 20 seconds.” It must have been quite the review process.

Several cancellations were challenged in court. In several cases, judges ruled that the administration was legally required to pay out the funds. One Supreme Court ruling compelled the Trump administration to resume around $2 billion in foreign aid funding for work already completed.

Only some of the funding has been restored since then. It seems that about a quarter of HIV program funding has been permanently terminated. But since thousands of USAID staff were laid off, even those programs whose funding was restored are still disrupted. Both USAID’s main website and PEPFAR’s data portal are still unavailable, as of April. A few weeks ago, the remaining staff at USAID were asked to “shred as many documents first, and reserve the burn bags for when the shredder becomes unavailable or needs a break”.

In some cases, research projects had already rolled out new testing methods or treatments and were collecting data – but funding for the final steps, like analysis, was cut. That means the entire study could now go to waste.

For weeks – sometimes daily – reporters at the New York Times, Washington Post, and others covered the disruptions, and I thought more people and governments would notice and act on it.

But then the UK government announced that we would also be cutting foreign aid, despite earlier campaign promises to preserve or even increase it. Instead of stepping up, we in the UK are following the Trump administration in making deeper cuts. Why?

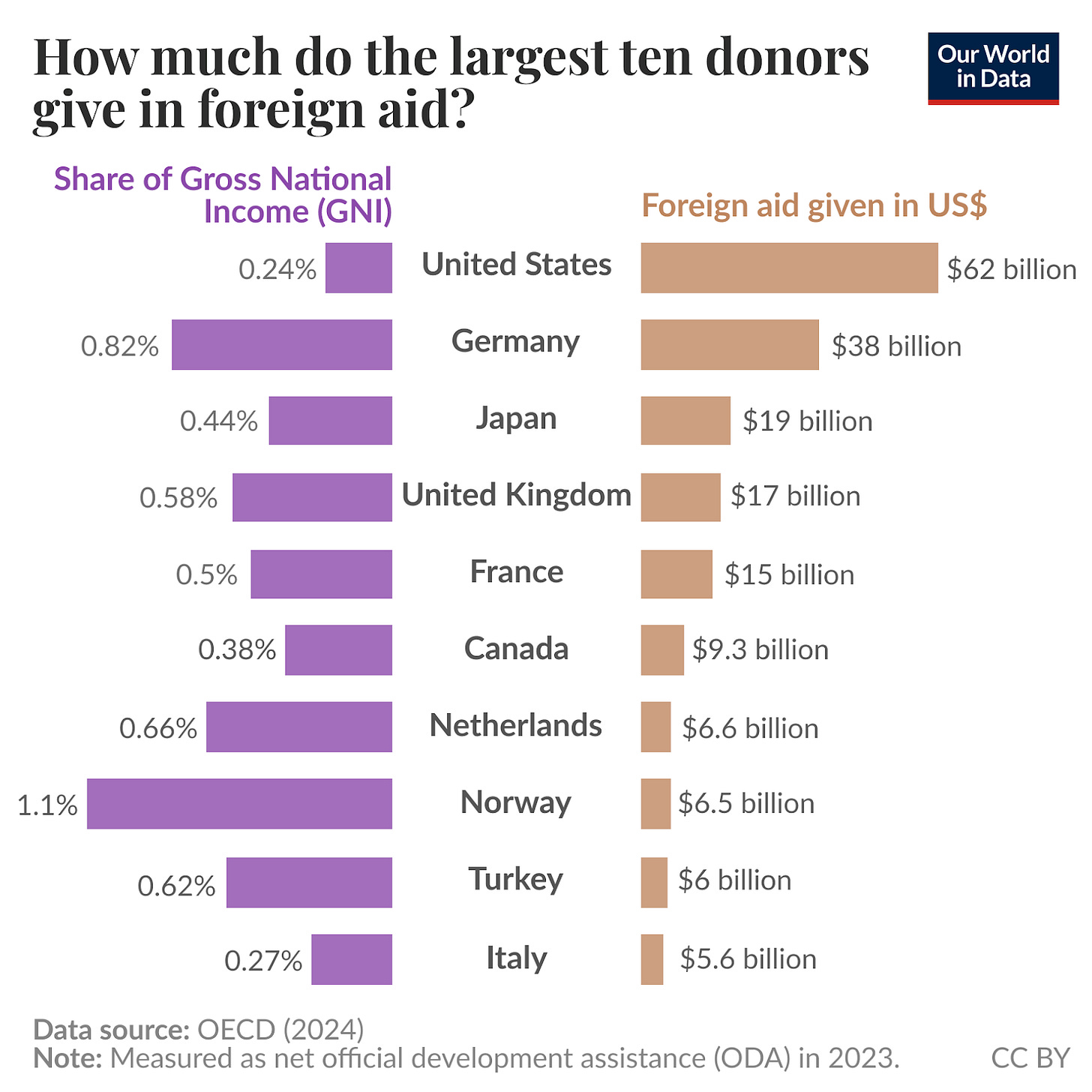

Somehow it still feels unthinkable that we’d let millions die preventably. Or we’d suddenly take away treatment people have relied on for years without debate, or any warning. Foreign aid costs a very small fraction of national income, and the US in particular spends relatively little, but in absolute terms, it makes a huge impact in poorer countries.

For a long time, I didn’t think personal charitable donations were “enough”, so I only donated occasionally as a one-off.

The better way I thought to make a difference was by fostering the policies, institutions, and innovation that made large-scale change possible: Trade and growth-oriented policies that make it possible for countries to invest more in healthcare and public health programs. Large aid-supported programs like PEPFAR, PMI, and Gavi that support millions of people. Breakthroughs like new antivirals or malaria vaccines, and innovations that can cut the cost of treatment dramatically, making it possible to save far more lives with the same amount of resources.

But this has made me realize how easy it is to take global health and humanitarian programs for granted, and I want to help however I can. Bridging the gap is urgent.

What’s the use of developing new technologies without the infrastructure – the people and resources – to deploy them? That’s what’s at risk right now. If programs shut down now, we could lose years of built-up infrastructure and expertise, and it’ll be very hard to bring them back. Millions of people are now at risk of losing that.

Worse is knowing that we’re on the cusp of rolling out new breakthrough treatments – like a new antiviral that prevents HIV with a 96–100% efficacy and only needs to be given out once per six months – that could have helped eliminate HIV transmission; and new malaria vaccines that could save a million children over the next few years.

The gap is difficult to fill with philanthropy alone and it’s terrifying to really think about. Imagine one in ten people around you have HIV, but they’ve suddenly lost treatment to this deadly disease that could kill them in years. That’s the sudden reality that millions of people faced during the freeze, and may continue to face, in some countries.

But that doesn’t mean that we can’t do anything about it. We don’t need to see this unleash the maximum possible amount of damage on millions of people. We can reduce that as far as we can, and I think we can keep some of these programs alive.

For one, I’ve decided to donate nearly 20% of my income this year, and I’ve committed to donating at least 10% of my income over my lifetime. On an individual level, this still pales in comparison to what’s needed, but I’d like to tell you how I thought about it.

I spent time thinking about how to donate that amount most effectively this year. Should I split my donation across multiple organizations, or give it all to one?

Right now, programs like the Foreign Aid Bridge Fund and the Rapid Response Fund, are helping to fill some of the gaps caused by the cuts. I think their work is really important. Both are trying to find some of the most cost-effective programs affected by the cuts, and raise philanthropic donations to direct to them. In case you’re interested in more detail, Sigal Samuel wrote a good article at Vox about them.

But recently, I also attended a talk by people working at Project Resource Optimization, who are experienced in cost-effectiveness analysis and have compiled a live list of high-impact USAID-funded programs affected by the cuts. They’re regularly talking to USAID-funded local programs and implementing partners to find out which have shut down, and which might still be saved.

I was very moved by their work and the thoughtfulness of their approach as well as their clarity on what was urgently needed right now. Rather than choosing larger programs or ones that are already well known, they compiled a “first cut” list of all potentially lifesaving programs in global health areas that were terminated. They then narrowed this down to an “urgent and vetted” list of those that they estimated were the most impactful, and cost-effective, meaning they are likely to save the most lives with a given amount of money, and crucially, which are urgently at risk of shutting down. Their list is online here.

I chose to donate 16% of my income to one of the smaller projects on that list. This was one where I think my donation would have the highest likelihood of helping it get across the threshold to keep it alive.

The one I chose was planning to expand clean water and sanitation in parts of Nigeria – that basic global health intervention known as ‘clean water’ that reduces the spread of diseases like cholera, rotavirus, polio, and many others. These infections can be deadly and are sadly common causes of child deaths in poor countries.

It’s also one that’s close to my heart because I believe that clean water and sanitation are still rather undervalued. A recent meta-analysis I’ve written about before looked at clean water treatment programs and their effects on child mortality across RCTs in 21 poorer countries. They found that clean water treatment, such as simple water chlorination, reduced child mortality by around 30% overall in the studies in these countries.

That’s a surprisingly large impact. But perhaps it seems that way to us living in countries with large-scale sewage systems and ubiquitous taps with clean drinking water that it’s hard to imagine how much it matters to people who don’t have it.

Then I donated another 3% of my income to cost-effective charities through GiveWell, which is also working to cover the shortfalls left by the cuts. In a recent post, they explained in detail how they’re responding in filling urgent gaps and expanding their core areas, with more funding towards malaria prevention and treatment, HIV testing, and healthcare worker training.

(For disclosure: I work at Our World in Data, one of many non-profits that receives some GiveWell funding.)

Although I believe funding is particularly urgent right now, I also think it’s important to think beyond the next few months and support these programs in the long term. That’s why I also signed up for the “10% Pledge” on Giving What We Can – meaning I’ll donate at least 10% of my lifetime income to effective charities – as a long-term commitment.

I wish I’d pledged earlier. If this post inspires you, or someone you know, that will make an even bigger difference. If you can inspire others too, maybe we could collectively keep more of these programs alive.

The impact of funding cuts is especially severe right now, so the sooner people take action, the better. But at the same time, I think it’s important to be strategic by supporting impactful programs that are providing essential services right now and are at risk of shutting down, as well as stable programs that can expand into these areas.

In the longer term, I think there are many ways to contribute. Global health and humanitarian programs rely on people doing lots of different types of work – from those providing healthcare directly to people running operations, handling logistics, writing grants, raising awareness, or doing research. You don’t have to work on the front lines or donate large sums as an individual to make a difference.

Beyond that, I’d like to see more governments have the moral courage to step up right now. Personal, philanthropic donations are just a small fraction of what governments can spend at a national level. We don’t all have to sit back and watch this horror unfold.

Where you can donate

Here is a brief list of some of the places you could donate.

GiveWell – A nonprofit that identifies and recommends some of the most cost-effective, evidence-based charities in global health. In response to the aid cuts, they’ve prioritized filling urgent funding gaps in malaria prevention, HIV testing, and healthcare worker training.

Project Resource Optimization – A team of researchers and cost-effectiveness analysts who built a live list of high-impact USAID-funded programs affected by the aid freeze. They’re talking regularly with implementing partners to identify the most urgent and cost-effective projects at risk of shutting down. On their ‘funding opportunities’ page, you can find programs directly affected and donate to them directly, or contact the research team for more information.

Foreign Aid Bridge Fund – An emergency philanthropic fund created to support lifesaving programs suddenly defunded by the foreign aid freeze. It focuses on bridging short-term gaps to prevent program collapse, such as HIV clinics in Kenya and Zimbabwe, health programs in Ethiopia, and disaster-resilient housing in Nepal.

Rapid Response Fund – Another emergency philanthropic fund launched by Founders Pledge and The Life You Can Save to quickly support top-rated global health and poverty programs facing sudden shortfalls. It provides emergency funding to keep high-impact interventions running during the aid cuts.

Gavi – A public-private global health partnership that provides vaccines to millions of children in low-income countries. The US, their largest donor (12%), withdrew all their funding for Gavi, putting global vaccination campaigns at risk.

If you want to sign up to a 10% Pledge from Giving What We Can like I did – and commit to donating at least 10% of your lifetime income to effective charities – you can do that here.

They also offer a more flexible Trial Pledge which can be 1–10% income for a fixed period of time, such as a year, for people who want to dip their toes into the water.

In case it bears repeating, this post and my newsletter as a whole reflect my personal views and not my employers’.

I hope you'll post lots of doable ways people can help on a regular basis. Half of the US is paralyzed with fear and learned helplessness. Right now we need lots of small opportunities to make a difference.

🔥🔥🔥 thanks for writing this and being public about your pledge.