#20: Many great things you missed this year

This week: Birth seasonality, causes of death across the lifespan, progress against HIV/AIDS & cystic fibrosis, very rare infectious form of Alzheimer’s, improvements in cholesterol, and more.

This is your favourite1 blog, Scientific Discovery. Check out the About page if you’re interested in why I’m writing this.

It’s been a while! But I’m going to get straight into it, because this post is long (and won’t fit on email).

If you like this, I hope you subscribe! As always, please point out errors if you spot any. I’ll really appreciate it, and I offer rewards for it, so you can “earn while you learn.”

Here we go!

The seasonality of births

Have you had a chart stuck in your head, years after seeing it? Mine is a heatmap showing that some birth months are much more common than others; meaning that birthdays aren’t spread equally over the year.

I couldn’t track down the chart I remembered, so I found the latest data from the United States and recreated it myself. Here it is, with data between 2007 and 2022.

As the chart shows, births tend to rise between July and September, in the United States.

These seasonal differences across the year aren’t small. In 2022, for example, February had the fewest births (275,000)2, while August had the maximum (335,000). This meant a range of 60,000 births, or about 10% above and below the average.

Researchers have actually known that births are seasonal for a long time. Data shows that birth seasonality varies between countries and has changed over time.

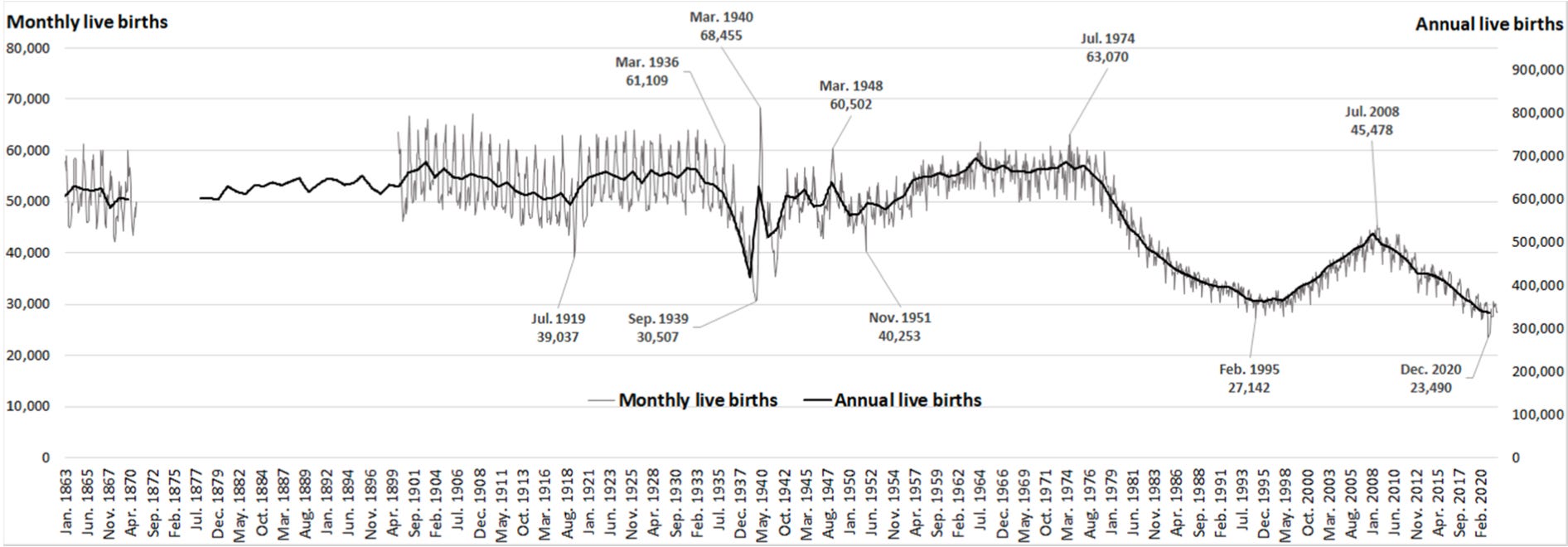

In a recent study, demographers looked at data from Spain, and found that the seasonality of births has shifted and declined over a century. I’ll take you through this with the chart below, which shows data since 1863 (!)

There are large fluctuations in births month-by-month, as you can see, which represent the seasonality of births.

The authors studied these seasonal patterns with Fourier spectral analysis, a method that’s often used to understand wave functions and time series data to uncover periodic patterns.

You can see that fluctuations in the monthly number of births have become smaller over time, meaning the seasonality of birth has declined. This is especially the case since around the 1940s and '50s.

In fact, the authors noted three breakpoints in the pattern — 1919 (corresponding to the flu pandemic), 1940 (the end of the Spanish Civil War), and 2020 (the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns). At these three points, the seasonal pattern of births noticeably shifted.

Another finding (harder to see in this chart) is that births in Spain have shifted from a spring peak to a summer peak. (More on this below.)

Something else I find interesting is the actual numbers of births themselves. It surprised me to see that births stayed relatively stable across the 20th century, during a period of population growth; that they declined so much during the 1970s and 80s; and that they rose from the 1990s.

But why are births seasonal in the first place? Multiple factors seem to contribute. For example, temperature and climate — researchers have previously found that hotter temperatures lead to declines in births nine months later. See this in the chart below.

On the right, you can see the effect of each 90ºF day (i.e. 30ºC) on the monthly birth rate nine months later. On the left, you can see how this effect is stronger at higher temperatures.

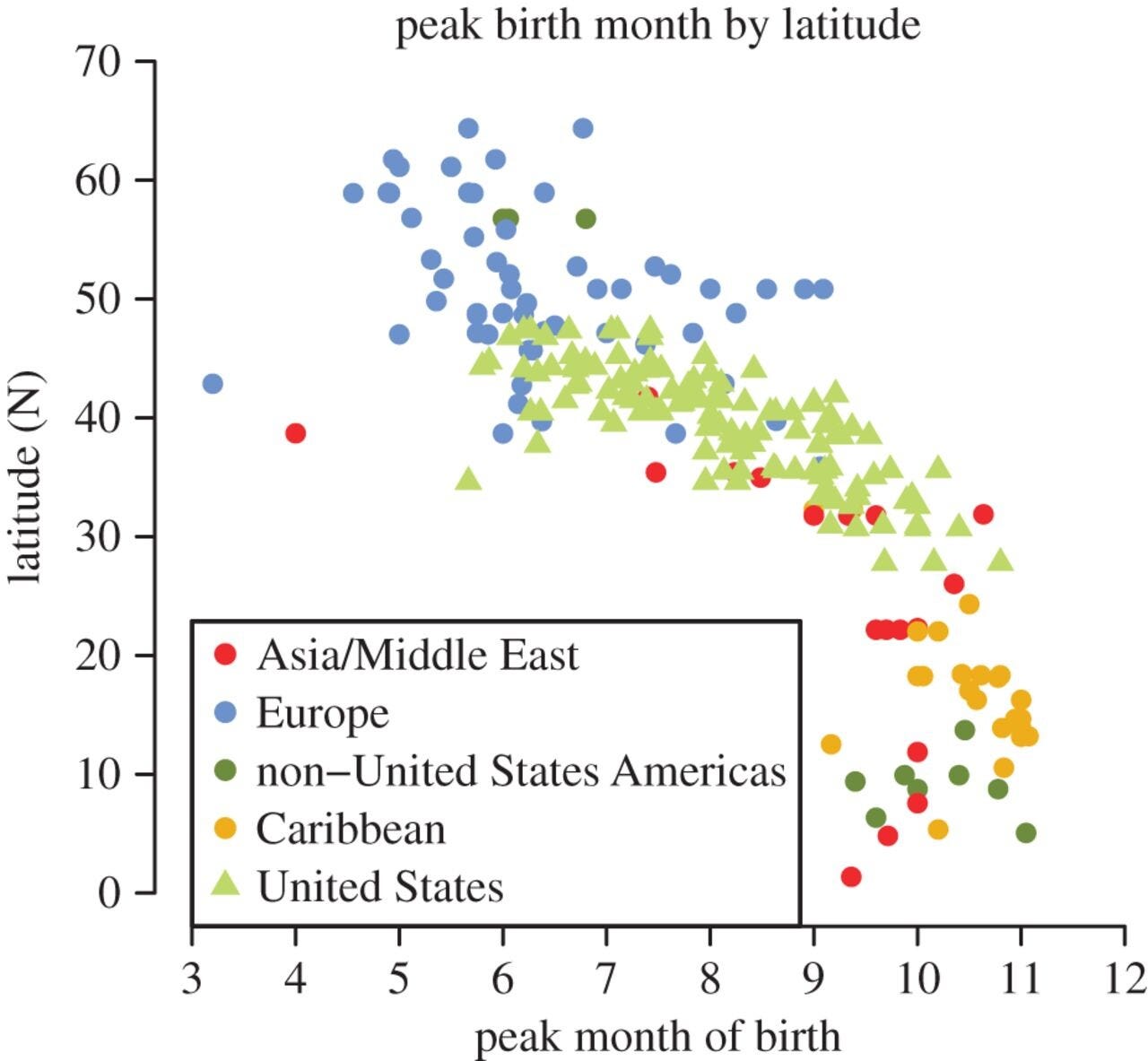

This might be why there’s a notable relationship between latitude and birth seasonality around the world, which is in the next chart below.

Each dot represents a different country or state (in the US), and I’ll describe it below.

You can see how countries in Europe (which are at higher latitudes) tend to have their “peak birth month” in the summer (around May to August). In contrast, countries in the Asia/Middle East and the Caribbean tend to have their peak birth month later in the year, in autumn or early winter. This pattern is also visible within the US — southern states have later peak birth months.

Aside from climate, the authors suggest various other factors that could also be relevant.

One is agriculture. For example, parents might plan to avoid births during the harvest season, when raising a child would have been more difficult. In the past, especially in places that had a large agricultural labour force, this could have been very relevant.

And we also now have better birth control and temperature control (such as air conditioning), which could have also helped reduce the seasonality of births over time.

It seems like there’s still much left to understand on this topic. I started reading about this out of curiosity, and didn’t expect to find the history behind it so interesting. If you’re interested in some more, here’s a link to the study.

So, if you think way back to the start of this post, I’d been thinking about a chart I had vaguely remembered and wanted to recreate. Now, here’s another one I’d wanted to see for a while, but hadn’t.

What do people die from, and how does this vary with age?

It’s common knowledge that cardiovascular diseases and cancers are the most common causes of death.

But this metric — “the most common cause” — is about causes of death across all age groups. Because older people have much higher risks of dying, their causes of death dominate deaths across age groups.

I hadn’t seen a satisfying way to visualize causes of death in different age groups all at once, which is important because we know that children and young people tend to die from different causes. But recently, I stumbled on this new and important paper on the causes of death we experience among our relatives.

It inspired me to make this chart, with the latest data from the United States, which shows the relative share of deaths from each cause, across all age groups.

You can see that, in childhood, in the US, the most common causes of death are ‘external causes’. This is a broad category that includes accidents, falls, violence, and overdoses, and is shown in red. But there’s also a notable contribution from birth disorders (in muted green), childhood cancers (in blue), and respiratory diseases (in cyan).

The share of deaths in childhood from cancers stood out to me. We’ve seen lots of progress against many childhood cancers over the last 50 years — notably in treating leukemia, brain cancers, kidney cancers, lymphomas, and retinoblastoma — but this is a reminder that there’s still further to go.

From adolescence until middle-age, ‘external causes’ are now the overwhelming cause of death. Around 80% of deaths at the age of 20 in the US are due to external causes. These result from causes such as accidents, violence, and overdoses.

At older ages, diseases rise in importance. Causes of death also become more varied, although cardiovascular diseases and cancers are the most common.

You might also be wondering about the brown category at the bottom, called ‘special ICD codes’. That’s a placeholder category in the system for deaths caused by new diseases — predominantly Covid-19, since the data spans 2018 to 2021.3

The chart we saw above looked at the relative share of deaths from different causes.

But if we want to understand how these trends arise, it’s more helpful to look at the death rate from each cause instead.

For example, if you were wondering why cancers appeared to decline after the age of 70, based on the chart above, the answer would be that, well, they actually don’t. The apparent decline of cancers is because cardiovascular diseases rise much faster with age than cancers, and thus make up a larger relative share. You can see this below.

The chart also shows that most causes of death rise exponentially with age.4

This includes blood disorders, cancers, cardiovascular diseases, digestive diseases, endocrine diseases, genitourinary diseases, infectious diseases, and several other categories, which each become exponentially more deadly with age. Covid-19, which falls under ‘special ICD codes’, follows a similar exponential trend.

But ‘external causes’ are one exception. They rise very suddenly in adolescence, are relatively stable afterwards, and then become exponential in old age.

‘External causes’ is a category that includes accidents, violence, overdoses, and falls, which might be a clue. My interpretation is that adults of many ages are likely to be exposed to these factors — but at the oldest ages, people’s vulnerability to dying from them rises exponentially. Of course, there are also some causes, like falls, that become more likely in old age.

I’ve written more about this topic here: How does the risk of death change as we age – and how has this changed over time?

Here’s a little summary of other great stuff I’ve read recently.

Research round up!

People with HIV who begin antiretroviral therapy early and continue it over the long term now face a life expectancy5 that’s almost the same as people without HIV. (Life expectancy after 2015 of adults with HIV on long-term antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Adam Trickey et al., 2023)

This new study estimates that women who began early antiretrovirals had a life expectancy of around 77 years, compared to around 81 in the general population.

Early treatment with antiretrovirals has been surprisingly effective. It reduces HIV’s ability to multiply in our bodies, leading to levels so low that they are undetectable by standard medical tests. At such a low level, the virus isn’t able to spread to other people either.6

Because of this, some countries including the UK are on track to effectively eliminate HIV transmission within the decade, as I’ve written about previously. And already, the US has effectively achieved the elimination of HIV transmission to infants.7

HIV incidence has been declining in the UK since around 2012. This can be estimated because HIV kills a type of white blood cell (CD4+ T cells). By counting how many of these cells people have, scientists can estimate how many of them have undiagnosed HIV. Source: Public Health England (2019)

New treatments for cystic fibrosis have massively improved life expectancy of people with the disease. (Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor projected survival and long-term health outcomes in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for F508del. Andrea Lopez et al., 2023.)

In the 1950s, infants and young children who screened positive for cystic fibrosis had a life expectancy of only 4–5 years. (Check out this great review if you’re interested in the history of cystic fibrosis treatments.)

But now, they have a life expectancy of around 72 years.

This estimate is based on simulation studies that use data on cystic fibrosis patients. Specifically, it looks at people who carry the most common CF genetic mutation, known as F508del, and also receive the combination treatment commonly known as Trikafta (or Kaftrio) at an early age.8

The combination treatment includes 3 drugs: elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (ELX/TEZ/IVA). The chart below shows the percentage of people with cystic fibrosis who would still be alive at each age, based on which treatment they receive.

There’s a great article in The Atlantic about how this has changed people’s lives.

Survival curve showing the projected survival of people with the most common cystic fibrosis genetic mutation F508del, shown by the treatment they receive. ELX/TEZ/IVA refers to the combination treatment called Trikafta/Kaftrio. LUM/IVA refers to lumacaftor plus ivacaftor, a treatment first approved in the 2010s. BSC refers to ‘best supportive care’, which can include daily nebulizers, lung physiotherapy, and other pills. Source: Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor projected survival and long-term health outcomes in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for F508del. (Andrea Lopez et al., 2023).

A very rare situation where Alzheimer’s disease was infectious, like a prion disease. (Iatrogenic Alzheimer’s disease in recipients of cadaveric pituitary-derived growth hormone. Gargi Banerjee et al., 2024) See also the STAT article on this study.

A recent study looked at people in the UK who had received pituitary growth hormone transplants while they were young (to treat conditions of short stature). They received these medical transplants from the brains of cadavers, between the 1950s–80s. (NB: cadavers are no longer used as a source of pituitary hormone; for decades, synthetic hormone has been used instead.)

A fraction of all the people who received these transplants developed dementia very early — in their late 30s or early 40s. Having dementia this early is very rare, even among ‘early-onset Alzheimer’s disease’ patients, who typically develop it in their 50s or early 60s.9

It turns out that some batches of the growth hormone from cadavers had been contaminated with amyloid plaques, which are a precursor to Alzheimer’s disease. The researchers looked specifically at which batches of growth hormone these very-early dementia patients received, and found that they were contaminated with the plaques.

With these findings, and other experimental studies in mice, there’s strong evidence that the contaminated transplants had ‘seeded’ the amyloid protein in people’s brains, which eventually propagated into plaques, leading to dementia. Similar developments have been seen in the past with other prion diseases, like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

I hope and wonder whether conceptualizing Alzheimer’s as a prion disease will help think of new ways to treat it, and to find treatments for other prion diseases as well.

Did you know that cholesterol levels have been gradually improving in the US? (US trends in cholesterol screening, lipid levels, and lipid-lowering medication use in US adults, 1999 to 2018. Yumin Gao, Lochan M. Shah, Jie Ding, Seth S. Martin, 2023.)

A recent study looks at trends in cholesterol levels and statin usage in the US population, using data from the NHANES, which is a large national study of health and nutrition in the general population.

The authors find that levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL-cholesterol (also known as ‘bad cholesterol’), have been declining, at a population-level, among people of the same age. You can see this below.

Age-adjusted trends in total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol in the United States. Data comes from the NHANES, a national study with cholesterol data from 50,000 people. Source: US trends in cholesterol screening, lipid levels, and lipid-lowering medication use in US adults, 1999 to 2018. (Yumin Gao, Lochan M. Shah, Jie Ding, Seth S. Martin, 2023). Why have cholesterol levels been declining? One reason is that more people take statins, which reduce cholesterol and are effective medications for cardiovascular disease. In 1999, around 15% of eligible US adults were taking statins, but by 2017, around 28% were.

Though this mechanism seems obvious in retrospect, the reason we can see a noticeable trend at the level of the population is because cardiovascular diseases are common in the population, and statins have strong effects in treating them, and there have also been improvements in screening and public awareness of these conditions.

There’s still a lot more I wanted to write about, but I’ll stop there because this post has become very long already, and who knows, you might have other things to do today.

Here’s some of the best stuff I’ve read & found recently.

Recommendations!

Making the micropipette — how problems with mouth pipettes led to the invention of micropipettes, although this shift happened later than one would imagine. This sentence stuck in my memory: “While mouth pipetting one night in the lab, Suovaniemi ‘almost swallowed a piece of rat’s brain,’” That’s one way to get a ‘taste’ of neuroscience!10

Aliens?? — “JHU scientists say that key evidence of an interstellar object was actually just a truck driving near a seismograph,” Every news story about aliens entertains me more than the last.

‘Failure at every level’ — a thrilling story about the downfall of Didier Raoult, who boosted hydroxychloroquine as a Covid treatment while conducting unapproved trials, ran 248 trials under a single ethics code, had 10 articles retracted, and has 50 more flagged for concerns.

Have you ever wondered how the windpipes of different insects compare to each other? Me neither. But recently, entomologists used micro-CT scans to visualize the windpipes of 30 different insect species in 3D, which I thought was pretty cool actually.

Visualizations of the windpipe of the Calopterygidae family, commonly known as ‘damselflies’, from micro-CT scans. Source: Comparative anatomy of the insect tracheal system, part 1. Introduction, apterygotes, Paleoptera, Polyneoptera. (Hollister W. Herhold, Steven R Davies, Samuel P. Degrey, David A. Grimaldi, 2023). A case study of a man who got vaccinated 217 times against Covid. He didn’t have side effects, has no sign of ever being infected by Covid, and had a normal immune response to other infections. Why stop at herd immunity when you can be the herd?11

The physics of flight — an incredible interactive explainer by Bartosz Ciechanowski, whose blog is amazing.

‘ERROR, a bug bounty program for science to systematically detect and report errors in academic publications’ — get paid for spotting errors in scientific publications! (Hey, you can do the same on this blog!)

10 technologies that won’t exist in 5 years — Jacob Trefethen’s list of technologies that are worth working on and achievable, but won’t exist in 5 years.

The Webb Telescope’s image of the Crab Nebula. ‘The Crab Nebula, also known as M1, is a supernova remnant: all that remains of an exploded star.’ How cool is that? NASA has an explainer on how their full-colour images are made.

Image of the Crab Nebula, by the James Webb Space Telescope. Here’s a nice article from Sky At Night magazine about it.

And… that’s all for now!

I have a busy few weeks ahead, but I’m trying to spend about an hour a day doing personal writing and dataviz, so hopefully you’ll see another post soon.

If you enjoyed this, I hope you subscribe and share this with your friends! As always, if you’ve seen any errors, please let me know, so I can fix them.

See you next time! :)

– Saloni

I mean, probably. I hope.

Bill Burke pointed out that February is around 10% shorter than the other months, which means it starts with a handicap towards how many births it has.

This could help explain the extra dip in February compared to other winter months.

You can see that around 7% of all deaths above the age of 40 between 2018–2021 were in this ‘special ICD codes’ category, which was predominantly Covid-19 in this period. This share includes data from two years before Covid-19 began.

This exponential rise with age is sometimes described as the “Gompertz-Makeham Law of Mortality”. Read more about this in my article: How does the risk of death change as we age – and how has this changed over time?

Life expectancy usually refers to ‘period life expectancy at birth’, which is a statistic calculated using data across the population in one single year.

The period life expectancy in 2022, for example, tells us the average lifespan of a hypothetical group of people, if they experienced the same death rates at each age of their lives, as the death rates seen in 2022 at each corresponding age group. Read more about this in my previous post: #19: Seven things you didn't know about life expectancy

Recent research finds that, even at detectable levels, where HIV is ‘stably suppressed’, it is untransmittable.

‘Effectively eliminated’ in this example refers to a rate of <1 new cases per 100,000 live births.

In the UK, as in several high-income countries, newborns are screened to see whether they carry cystic fibrosis genetic mutations. In the past, the condition was tested for by using a ‘sweat test’, which measures the amount of chloride in their sweat. Because kids with cystic fibrosis have a genetic mutation that prevents normal transport of chloride across cell membranes in various organs, it leads to having higher levels of chloride in their sweat, as well as thicker mucus in their lungs and digestive system (leading to breathing difficulties) and other complications.

One exception to this is people with Down syndrome, who tend to develop Alzheimer’s in their 50s, but can also develop it in their late 40s.

This pun was written by chatGPT.

Certainly! This pun was also written by chatGPT.

Birth seasonality is interesting. Not the least for those of us who are trying to avoid crowded maternity wards.

I have six children. Three of them were born in November. Two were born at the end of October and one in the middle of January.

There are several reasons behind this seasonality:

*The first months of pregnancy make me sick and tired. I don't want those months in the summer, because then I want to work.

*The last months of pregnancy are also not pleasant in the summer.

*Maternity wards are crowded in the summer because people have more babies then and staff are on holiday.

*Taking care of a newborn is a nice winter activity. In the summer, it is nice for the baby to crawl outdoors.

Hi, Saloni. I've been enjoying seeing your posts on Bluesky and finally made the leap over here to subscribe and start checking out your posts. I really enjoy your writing and presentation styles as well as your attention to detail and your obvious enjoyment and enthusiasm in sharing various things that you are interested in. So, thank you for putting your interests and skills to work to help the rest of us learn more about new research and topics.

There's a lot of interesting stuff in this #20 post and it would, I'm sure, be interesting to follow some of your links to delve into even more stuff, but I'm not going to have the time to do that now. I've got some in-progress political research topics that I need to get back to, being as we're in our presidential election year here in the US.

I did notice that there is a missing word – "see" – in the part where you talk about "why are births seasonal in the first place?" "On the left, you can SEE how this effect is ...."

There is also one place where you have an extra word, but I didn't immediately make note of where it was and now I can't find it again. Sorry.