#1: Great new scientific research – condensed

This week: New RSV vaccines, new trials, and an ancient epidemic mystery being resolved. And this is only the beginning.

This is my first-ever post of Scientific Discovery, a weekly newsletter where I’ll share great new scientific research that you may have missed. Today, I’m just going to jump straight into it – but check out the About page if you’re interested in why I’m doing this.

Highlights

#1: The first working vaccines against Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is a big cause of infant deaths worldwide. It’s highly contagious, spreading through droplets and nasal secretions – there are new global outbreaks each year, and people are repeatedly infected. It’s more severe in infants and the elderly – in the US, it’s estimated to cause half of respiratory hospitalisations in infants, and worldwide, around 6% of child deaths from lower respiratory disease.

Unfortunately, treatment is expensive and uncomfortable – largely limited to supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation. Developing a working vaccine has been a priority since the 1960s. But until recently, this has been elusive.

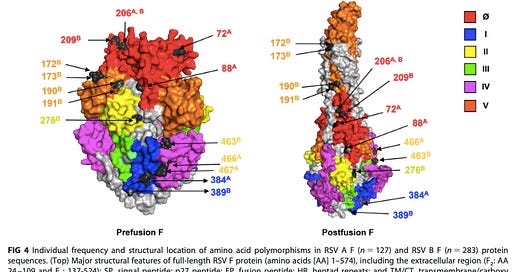

One challenge was that the virus changes its shape as it fuses with cells before entering them. In the past, RSV vaccine candidates contained the “post-fusion” structure of a virus protein, meaning that people’s immune cells are less able to recognize and block the virus when it initially appears in the “pre-fusion” structure instead.

This changed in the last decade, as scientists figured out how to recreate and stabilise the pre-fusion virus protein.

In case you weren’t aware, this trick was also crucial in designing many of the Covid-19 vaccines, and it was based on research by some of the same scientists.

Earlier this month, GlaxoSmithKline announced their pre-fusion RSV vaccine was successful in phase III trials, which included 25 thousand elderly participants across 17 countries. And this week, results were published of another pre-fusion RSV vaccine funded by Pfizer, from their phase II challenge trial of young adults.

Challenge trials like this are extremely useful, because – as everyone in the study is exposed to the virus – they need fewer participants to determine whether these vaccines are effective. They can also focus on adults, who are less likely to develop severe disease, and observe the difference between vaccine and placebo in a much shorter length of time.

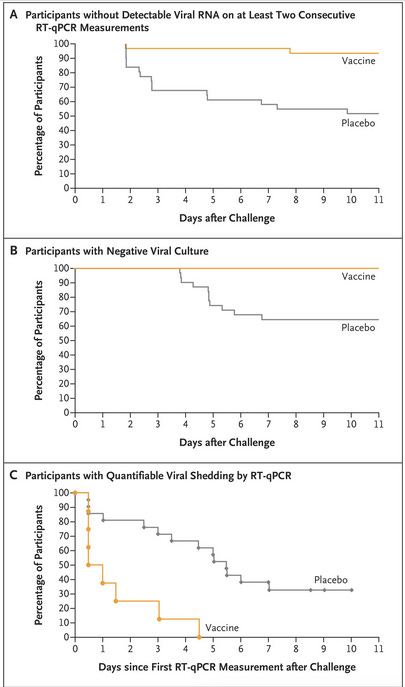

Here are the results from the challenge trial funded by Pfizer. The charts pretty much speak for themselves. These are vaccines with high efficacy; reducing the chances of detectable infection by 75%, and the chances of disease even more.

After decades of research, we will soon have not just one working vaccine against this fatal disease but several.

More links

#2: The origin of the Black Death

Paper: The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century central Eurasia (Spyrou et al., 2022)

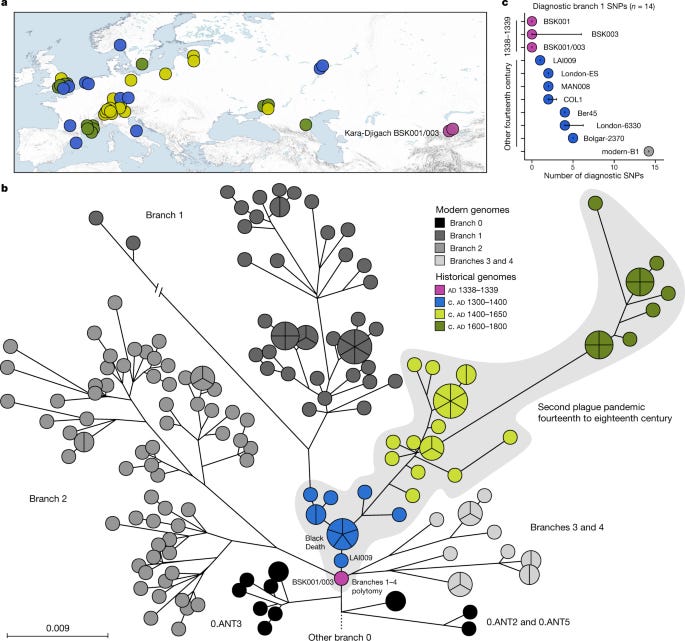

The bubonic plague, which spread through Asia, Europe and Africa in the 14th century, is the most fatal pandemic we know of in history. The bacterium Yersinia pestis was long suspected to be at fault, but this was only confirmed by genetic research in the last decades.

Although Y. pestis is also believed to have caused earlier pandemics as well, it’s estimated that most strains of the bacteria that exist today come from the Black Death (1346–1353).

So where did that begin? This new study places its origin in modern day Kyrgyzstan. This comes from ancient DNA samples from newly analysed exhumed bodies that were buried in cemeteries in 1338–39. Morbid!

[Update: This was in the news recently, which is why I decided to include it. But see this long and detailed critical thread on the paper and the authors’ choice of samples.]

#3: Vitamin C is harmful for patients with sepsis in intensive care

Paper: Intravenous Vitamin C in Adults with Sepsis in the Intensive Care Unit (Lamontagne, 2022)

This new randomised controlled trial shows that patients who were hospitalised for sepsis had a higher risk of organ dysfunction or death if they were given Vitamin C rather than a placebo.

I was just going to leave this here by stating the obvious: sometimes vitamins are good for you, but sometimes they are not. But this is more important than that.

Finding out what doesn’t work is important because it means we can shift our time and resources away from things that don’t work, towards things that do. Randomised controlled trials are a great tool to help us do that, as I’ve written about before.

#4: At what age do diseases begin and how do they affect life expectancy?

Online atlas: The Danish Atlas of Disease Mortality.

For a number of reasons, it tends to be difficult to estimate the age when diseases begin, or when they are diagnosed, or how they affect your mortality at different ages.

For rare diseases, it’s difficult to get a large enough sample to make these estimates precisely. And in many countries, crucial data from patients – such as information about which diseases they were diagnosed with and when – is lacking.

But not in Denmark – which has a comprehensive registry of diagnostic data from everyone in the population.

This paper and the accompanying online atlas are extremely cool. They let you explore all sorts of questions, like the ages when people get diagnosed with tuberculosis, how this affects their risk of death, and how many years of their lives they are expected to lose.

Recently, for Our World in Data, I wrote about the same team’s earlier research, which showed that depression is being diagnosed earlier than in the past – there are several reasons to believe this is because of shorter delays in diagnosing people after they develop mental health conditions, as this trend is seen in several conditions including anxiety disorder and depression.

Even more links

Here are some more studies from the last few weeks.

Results from a clinical trial of a new anti-obesity drug, Tirzepatide. It leads to a 20% reduction in body weight (!) in obese patients when taken once a week for a year. Jastreboff et al. (2022)

See also Stephan Guyenet’s article The future of weight loss explaining the discovery of these new anti-obesity drugs for Works in Progress.

Smiling actually makes you feel happy. This is a great study showing that this is not just a placebo effect – here’s a Twitter thread from the author explaining it. Coles et al. (2022)

Why wasn’t the steam engine invented earlier? (Howes, 2022) An incredible deep-dive by the great historian of innovation, and my friend, Anton Howes.

The risk of dying from various respiratory diseases (Covid-19, influenza, MERS and SARS) increases dramatically with age, but is also much higher in early infancy. You can see some fascinating trajectories in their paper here. (Metcalf et al., 2022)

That’s all for my first post! I was planning to start with a welcome post, but then I realised it’s probably a better idea to just demonstrate what you’d get out of subscribing to this.1

This week’s links are mainly about disease, but I plan to share research from other areas I’m interested in as well. That includes psychology and psychiatry, genetics, demography, empirical economics, epidemiology, and various areas of social science – but only topics that I’m comfortable with and confident in writing about. If you spot any errors or think I’ve missed anything, please let me know!

I hope you subscribe!

If you don’t know me from Twitter, here’s a short bio of myself. I’m a founding editor at the online magazine Works in Progress, a researcher on health for Our World in Data, a commissioning editor at Stripe Press, and a final year PhD student at the University of Hong Kong and King’s College London. It can be a little exhausting to think about.

If you’re interested in reading about why I’m doing this, check out the About page.

Thanks for doing this, Saloni. It's such an accessible and refreshing alternative to the often bizarre and butchered mainstream coverage most of us are used to!

Great job, Saloni! I’m impressed that you have the time to do such thorough summaries. Keep it up!